To Kill a Mockingbird is set between 1933 and 1935, during the time of the Great Depression, which had already persisted for four years. People were scrambling to find work, with two million being homeless. The middle class was rapidly declining, and some resorted to extreme measures, such as suicide. To rebel against the harsh times, people had fallen into a deep abyss, disoriented and lost, feeling as though they had reached the end of the road. With little to do and even less hope for the future, the entire nation was plunged into a dark, demoralizing low, struggling to find a way forward.

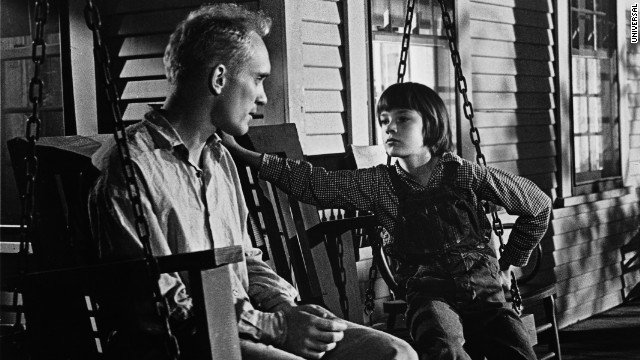

Scout, as Atticus’s daughter and the narrator of the story, shapes the film’s rhythm through her perception of the world and her emotional fluctuations. Like many children, she believes in ghosts and monsters and is fascinated by such tales. She wholeheartedly accepts the terrifying rumors about Boo Radley, describing him as a ghostly figure with bloodstained hands, a diet of small animals, a horrifying scar on his face, missing teeth, and bulging eyes. This fear gradually transforms the Radley family into a symbol of a strange, tragic household. The Radleys’ quiet house becomes the perfect setting for terrifying fantasies, appearing either eerily silent, as if concealing some evil, or occasionally emitting low, unsettling laughter that sends chills down one’s spine. Boo Radley becomes the embodiment of terror, lurking in the dark shadows of Scout’s nightmares, grinning and howling with blood dripping from his mouth. Therefore, when she rolls into the Radley yard in a tire, she was frozen in fear. For the children, daring to explore Boo Radley’s yard is a part of their games, but Atticus puts a stop to it. As they are too childish to fully understand the truth behind the rumors.

Whenever Scout feels anger with life and conflicts with those around her, it becomes a growth experience, helping her better understand the complexities of life. She dislikes school after being scolded by Miss Caroline, but Atticus teaches her to empathize with others. Although she feels that traditional teaching methods have “cheated” her out of something, Atticus encourages her to learn what is valuable from them. Scout struggles with controlling her emotions and often resorts to solving problems with her fists. When she is angry with someone, she can be extreme, saying things like, “I hate you, I despise you, I hope you die tomorrow!” In a way, the adults’ treatment of Black people reflects a similar extremism, devoid of reason and basic moral judgment. They hate, and so they wish for their destruction. The children, Scout in specific, demonstrates the unfiltered flaws in human nature which mirrors the shadows of the adults around them, showing similar anger to life and people of different race.

Eventually, Boo Radley dispels the fear and prejudice the children held against him through his kindness and genuine heart. When the shadow of terror fades, Scout suddenly feels she has grown up, no longer afraid of believing in so-called “ghosts, hot steam, spells, or signs.” She learns to use her judgment to analyze situations rather than blindly trusting rumors and biases. Boo Radley not only gifts them two carved wooden figures, a broken watch and chain, and a small knife but also saves their lives and quietly accompanies them on their journey of growth.

In the South, there is a saying: “It’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” The novel/film To Kill a Mockingbird, derives its title from this saying, though it omits the part, “it’s a sin.” As a result, the title appears more like a neutral statement of fact, but beneath its calm surface lies a powerful indictment. Mockingbirds do nothing but sing beautiful songs; they harm no one, destroy no gardens, and damage no barns—they simply sing to bring joy to their listeners. Thus, to kill such an innocent creature is a sin, a senseless act of cruelty.

In the film, there are two harmless “mockingbirds” misunderstood by people —one is Scout’s neighbor, Boo Radley, and the other is Tom Robinson. The former is a victim of neighborhood gossip and prejudice, while the latter is a casualty of the deep-seated racial discrimination prevalent in American society at the time.

From the beginning, the story does not explicitly explain the reason behind the events, but through the serious conversations among adults and the conflicts between Scout and her classmates, it becomes clear that Atticus is preparing to defend a Black man. This situation seems capable of igniting a war at the town at any moment, as friends and neighbors gradually reveals the anger, hatred, and racism within themselves. The tranquility of the Southern town is inevitably shattered by this case.

During their visit to Tom Robinson’s home with their father, Jem and Scout experience the true horror of the situation for the first time. Jem sits alone in the car in the dark, waiting for Atticus, when Mr. Ewell suddenly appears out of nowhere. Hunched over and drunk, he lunges toward the car window, peering sneakily at the sleeping Scout before pressing his face against the glass and glaring menacingly at Jem, his features twisted and his false teeth bared. Terrified, Jem feels a genuine sense of oppression in the confined space of the car—a threat from his own kind, no longer just the stuff of rumors but a real-life “monster” before his eyes. Fortunately, Atticus arrives just in time, standing firmly in the center of the scene like an unwavering guardian, his expression serious and his brow slightly furrowed. Upon seeing Atticus, Mr. Ewell immediately shrinks back, muttering “n****r-lover” through clenched teeth before slinking away. Every time he appears, he carries malice, yet he always retreats at the sight of Atticus, as if his insults are merely a cover for his own cowardice. Even after the trial, when Mr. Ewell spits in Atticus’s face, Atticus responds with quiet dignity, simply wiping it away. The calmer Atticus remains, the more Mr. Ewell is left humiliated and exposed.

On the eve of Tom Robinson’s trial, the fear and tension brewing in the hearts of Maycomb’s residents finally erupt. No one but Atticus is willing to give a Black man the chance to defend. Atticus stands guard at the entrance of the jail, the lightbulb above casting a calm glow. Cars converge from all directions, and the townspeople, usually kind and friendly, now appear menacing. They are no longer rational individuals but a mob, attempting to break through Atticus’s defense and tear apart the Black man inside the jail. Atticus shows no anger or agitation. He even stops Scout from kicking at the crowd. Later, he says that the presence of the children tamed the “savagery” of these people, but the steady, righteous power Atticus embodies cannot be ignored or questioned. Without resorting to violence or force, he makes the mob retreat on their own. True strength lies not just in physical or material power but in the power of the spirit. People inevitably feel awe toward such individuals because he possesses the courage, perseverance, and civility they lack. When everyone else is blinded by anger, driven to madness, and indulges their desires, they fear those who, like Atticus, have a clear purpose and dedicate their lives to fighting for what is right.

The story of the injustice persecution of black people like Tom Robinson is not fabricated but rooted in the harsh realities of the time. In the 1930s, in the Southern states of America, interracial relationships between Black men and white women were criminalized. As a result, when many white women were suspected of having relations with Black men, they often shifted blame by accusing them of rape. A notorious example is the case of the “Scottsboro Boys”: two white female textile workers accused nine Black youths of assault, leading to their death sentences. All subsequent appeals failed, and the case only concluded when the last victim died in prison. When the truth was finally revealed, public outrage erupted, sparking a broader struggle for Black civil rights.

The psychological impact of the Great Depression on America cannot be simply explained by the word “poverty.” A series of tensions were simmering beneath the surface. President Hoover’s policies at the time were flashy but ineffective, filled with empty rhetoric and hollow promises, leading many newspapers to accuse him of lying. The nation was in decline, and even financial magnates were timid and short-sighted, their pessimism paralyzing progress. People lost faith in everything, feeling isolated and unsupported. With a government that seemed powerless, public confidence hit rock bottom. Repeated failures left them hopeless about the future, and in such a climate, social issues became increasingly pronounced. Like Scout in the film, their anger was always on the verge of erupting, ready to unleash pent-up resentment at any moment. It was in this atmosphere of complex emotions that victims like Tom Robinson emerged.

It is in this very moment that Atticus represents true justice, untainted by societal prejudices. He stands as a symbol of strength, quelling the fears within people’s hearts amidst the backdrop of economic depression, racial strife, and other challenges of the era. Therefore, Atticus also represents Harper Lee’s vision of an ideal figure capable of guiding American society toward a better future.